Written by Dr Catherine Bishop, Macquarie University

To celebrate Women’s History Month in 2020, the Royal Australian Historical Society will continue our work from last year to highlight Australian women that have contributed to our history in various and meaningful ways. You can browse the women featured on our webpage, Women’s History Month.

Anne Johansen (née Lock), 1937 [photograph courtesy Mrs B Bradshaw]

This was probably the most dramatic period in Annie Lock’s missionary career, which spanned over 30 years and four states and territories. She was a faith missionary, which meant that she was not paid and could not solicit donations directly, relying on God to provide all her needs. This understandably meant that she was fairly impoverished, although she became adept at writing letters and reports requesting ‘practical’ support in very specific terms. For example, in 1933 she told her supporters that she had ‘an offer of a nice staunch horse for £12’, asking that they join her in prayer so that God might provide the funds. Needless to say, He did.

Born in 1876 in Riverton, South Australia, in the middle of a large Wesleyan farming family, Annie left school early and was a dressmaker before attending missionary college in Adelaide and then joining what would eventually become the United Aborigines Mission (UAM). Her career started predictably enough: after a brief apprenticeship she was put in charge of the mission at Sackville Reach between 1904 and 1906, before being sent to Forster further north. She looked after children, preached services, taught school and acted as an intermediary when required. In 1909 she was sent to Perth, where she became matron of Dulhi Gunyah ‘Orphanage’, caring for children ‘collected’ by local police, as well as some who were sent by their parents for an education.

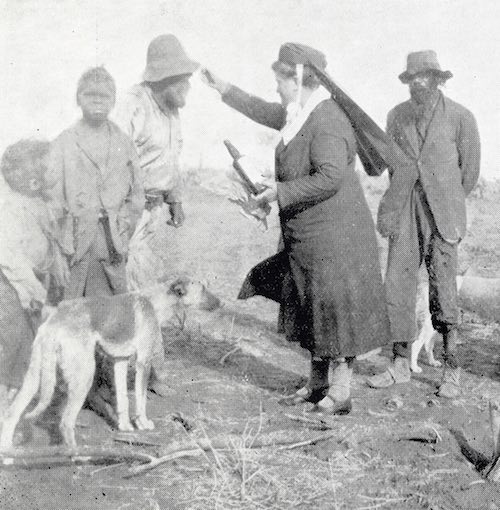

Photograph from The ‘Good Fella Missus’ by Violet Turner, Adelaide: United Aborigines’ Mission, c.1930

In 1912 Annie turned 36 and began to go off piste. As one colleague later put it, ‘God had endowed her with qualities which make for pioneering’, adding, not awfully tactfully, ‘It was soon found that she had a way of her own which would necessitate her working alone’. Annie established a mission station at Katanning in the south west of WA, and was essentially responsible in 1915 for the removal of people from the town reserve to Carrolup, which became one of Chief Protector A.O. Neville’s notorious ‘great reserves’, to which Indigenous people were forcibly sent. By then Annie had moved on, unable to work with her new colleagues, going north to Sunday Island. Here she worked (this time successfully) with the equally eccentric independent missionary Sydney Hadley. She developed an interest in Indigenous culture, although this also manifested itself in her collecting Indigenous artefacts and later selling them to the West Australian Museum to help fund the mission.

The extreme climate of the far north necessitated Annie’s removal south. After a year’s furlough she travelled up to Oodnadatta in 1924, founding what would become one of South Australia’s best-known children’s homes, Colebrook Home. This home for ‘part-Aboriginal’ children would become synonymous with the ‘Stolen Generations’, particularly after it moved south to Quorn and then the outskirts of Adelaide. As ever, Annie did not cope with sharing authority and when assistants were sent to Oodnadatta, she moved on. This was when she went, against the express wishes of the missionary society to Central Australia, where she had an uncomfortable time as we have seen. Her sojourn in the north improved when she moved to the Murchison Ranges, spending two years here looking after a number of children. The son of one of those children recalled decades later that his mother spoke fondly of Annie Lock, she taught them ‘right from wrong’ and, significantly, because she was on country, mothers could visit their children. Such memories complicate the story of missionaries and Indigenous children, particularly when one considers Annie Lock’s own words at this time: ‘the only thing I can see is to get the children right away from their parents’. This is a story of contradictions.

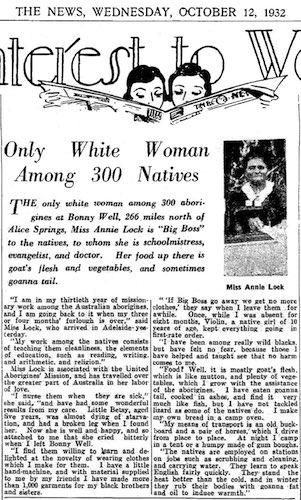

Page image from the National Library of Australia’s Newspaper Digitisation Program

Without any support from the UAM, Annie Lock’s time in Central Australia was necessarily limited. In 1932 she left, never to return. Instead she took an intrepid 500 mile buggy trip across the desert west to Ooldea, where, with the full support of both the South Australian government and the UAM, she established Ooldea Mission at the Soak. She fought with Daisy Bates, who considered her claim jumped, infuriated her fellow workers and found the Aboriginal people ‘the cheekiest I have ever worked with’. After she was attacked by one man because she refused rations (he argued, with some justification, that she had no right to withhold them) and disciplined his daughter by hitting her, it was clear that it was time for her to leave. In 1937 she retired from the mission aged 60 and astonished her colleagues by getting married. For the next six years until her death in 1943, she and her Plymouth Brethren husband, retired bank manager and widower James Johansen, tripped around Eyre Peninsula evangelising to white people.

While one may not admire all of Annie Lock’s actions or opinions, one cannot help but have respect for her courage, perseverance and the fact that she offered a friendly hand, albeit with strings attached. She was a significant figure in Australian history, one of an army of female missionaries who had profound effects, both positive and negative, on generations of Indigenous people. Lest we forget.

For more about Annie Lock’s extraordinary life, both good and bad, look out for Catherine Bishop’s forthcoming biography in 2021.

0 Comments