The epidemic affects remote Bundella

Contributed by Elizabeth Thomas

The extract below was first published in Vanished Land: Life on the Liverpool Plains 1873-1950, a self-published family and local history by Elizabeth Thomas, which appeared in 2013. It is reproduced here with her permission.

Background information

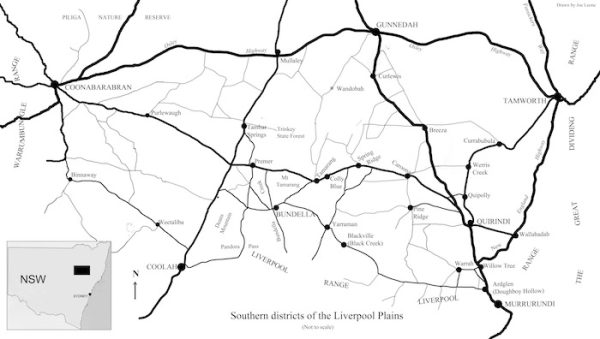

My mother’s family lived at the remote village of Bundella on the southern edge of the Liverpool Plains, some 250 miles north of Sydney. In 1919 the village consisted of four buildings: one house, one hotel, one church and a corrugated iron community hall. The house belonged to my grandparents. They ran the general store and the Post, Telegraph and Telephonic Office, all of which were attached to the house. It was 50 miles to the nearest town, Quirindi, where the closest railway station was to be found, and the hospital and doctor. Reaching town was an arduous journey of many hours along dirt tracks in the buggy. My mother, Jean Ewbank (1912–2005) grew up at Bundella. In the extract below I quote several times from her unpublished journals in which she recalls the Spanish flu epidemic of 1919.

Spanish flu in the bush

Bundella & District Map [Image courtesy Elizabeth Thomas]

In Quirindi, schools were closed, people were instructed to wear masks in public and there were to be no public gatherings. The hospital was isolated when the first case of pneumonic influenza was admitted. On 21 February 1919, a large notice had appeared in the Quirindi Gazette headed ‘Influenza Epidemic’. Free inoculations were to be given to the people of Quirindi at the Council Chambers the following day. ‘Delay is dangerous’, the notice warned. Dr Mead assisted by his wife and Matron McInerney gave the inoculations. The Half-Time Schools at Bundella and Bundella Creek did not close their doors because of the epidemic. However, people in the area were, in July, instructed to attend an inoculation clinic at the Royal Coolah Hotel, just down the road from the Bundella Store. My mother remembered the occasion:

A doctor came from Quirindi with a nurse to render this service at the hotel. A month later a booster shot was given and we thought that surely we were now immune. Before long our mother was stricken with the dread influenza and was confined to bed for six weeks. I went down with the flu but after ten days or so, was up and about but had missed two week’s school.

My grandfather, Jack Ewbank, found himself in a difficult position with my grandmother, May, seriously ill, five children to care for, Springrove (their small grazing property up in the hills) to run and the Store, Post and Telegraph Office, and telephone switchboard to manage. Charlie Coward worked for Jack at Springrove. He was a reliable young man, partly Aboriginal. My mother wrote:

Charlie now came to help Dad in this emergency, turning his hand to anything: cooking, washing, helping with homework, killing the pig. He never came into the sitting room but we could hear him banging pots and pans in the kitchen as he worked.

Jack Ewbank and Jean Ewbank right c.1920 [Image courtesy Elizabeth Thomas]

One day there was a knock on the store door and Mrs Jim Donoghue [May’s friend Annie] from Tamarang, tall and dressed all in black, entered and spoke to us in a whisper. Then Dad opened the bedroom door and ushered Mrs Jim in. That was, I think, the only visitor our mother had during her illness as people wisely kept away from the contagion. But the clouds rolled away. Before the spring was over, Mum was sitting at the head of the table once more and life resumed in the house behind the Store.

Friends later asked Jack why he hadn’t taken May to the hospital in Quirindi. His response had been, ‘Well, if you went to the bloomin’ hospital, you usually didn’t come back!’

References:

Durrant, Dorothy, Quirindi 1900–1919: Confidence and Patriotism (Nemingha, Dorothy Durrant, 1996).

Ewbank, Clare Jean Macdonald, unpublished journals (in possession of her daughter, A. Elizabeth Thomas), vol. 7, pp 60, 161, 162.

Quirindi Gazette.

The Sydney Morning Herald.

© Copyright A.E. Thomas 2013