The 1918-19 Pneumonic Influenza in Goulburn

By Madeline Young, Local Studies Assistant at the Goulburn Mulwaree Library

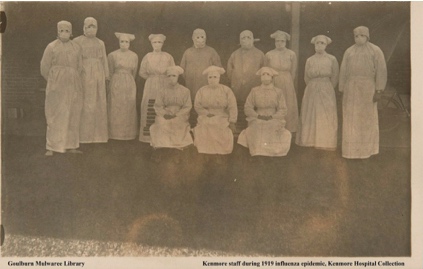

Nurses at Kenmore Mental Hospital during the influenza pandemic, Courtesy of Goulburn Mulwaree Library.

Australia, due to its location, had months to prepare for a probable outbreak of pneumonic influenza. Countries such as New Zealand, the US and British-controlled nations were ravaged by the disease in 1918, giving Australia a chance to learn from successes and mistakes of other nations. Despite strict quarantining regulations imposed by the Federal Government in late 1918, the pandemic came ashore in January 1919 in Melbourne, Victoria. [2]

Due to the Commonwealth’s willingness to enforce strict containment measures to combat the spread of the disease, [3] and the distribution of a free vaccine created by the newly established Commonwealth Serum Laboratories to over 3 million people, [4] Australia had a relatively low mortality rate when compared to other countries. According to State Records and Archives of New South Wales, pneumonic Influenza killed 6387 residents of NSW and up to 20,000 cases were reported in 1919, though the actual number is probably far higher. Crowded metropolitan areas like Sydney suffered greatly through the epidemic; with low socioeconomic areas hit the hardest, possibly due to wartime financial conditions lowering the standard of living. [5]

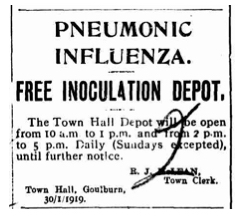

Goulburn was quick to ensure that all possible preparations were made for the spread of the virus. An inoculation centre was opened at the Town Hall on January 30, and in the following four days, 2908 people were inoculated with the vaccine.

Advert taken from the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 30 January 1919.

Despite the proactive stance of the town officials, there was still some resistance from the public. All race meetings were to be suspended, due to the close contact of the public at horse racing events and the fact that it would bring people from infected metropolitan cities to the area. However, representatives of Race Club came to a special meeting of the Town Council to appeal the ban suggested by the Minister of Health, given that no other enclosed entertainment in town, namely the picture theatres, had been subject to gathering restrictions. Council relented, and race meetings could continue as long as face masks were worn by the public. [8] This reluctance to ban close-quarter entertainment was echoed throughout New South Wales during the first, and less lethal, wave of the pandemic.

Despite being a central hub, Goulburn did not suffer its first case of pneumonic influenza until March. Earlier in February, a retired railway man named Peter Moran had come down with a particularly malicious variety of influenza, resulting in the patient being isolated in hospital and his household being quarantined, [9] but he was released on the 3rdof March with a clean bill of health and public assurances that he did not suffer from pneumonic influenza. [10]

John Stead, a labourer from Redfern, became Goulburn’s first registered case of pneumonic influenza, arriving in Goulburn from Sydney on March 18, 1919. Two days later, he was quarantined in the specialist isolation ward in the Goulburn Hospital. From this point on, the epidemic would slowly take hold of Goulburn and its surrounds. Adding to the problems faced by officials, was the outbreak of an extremely virulent form of ordinary influenza that was striking down a large portion of the population. While not deadly, town officials were exercising extreme caution, and any illness presenting like influenza resulted in strict quarantining orders.

On March 29, a labourer from Cook’s Cutting named John Joseph Donnolly was admitted into quarantine, becoming Goulburn’s second case. Two cases arose in Braidwood, and by early April, several more sufferers were put into isolation, including Eva May Strangman and her newborn infant, Evelyn. Within days of entering the isolation ward, both Eva May and Evelyn would become the first victims of the influenza pandemic in Goulburn, dying on the 17thof April, 1919. Eva May was only 32. [11] Mortality rates were highest in pregnant women, and only marginally more positive in post-partum women. [12]

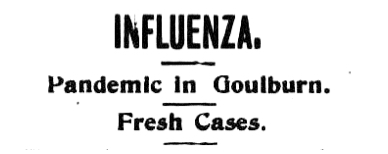

The 24th of April was a turning point for Goulburn and the influenza pandemic. The city was officially declared infected on this day by government proclamation, and justifiably so. There were eleven fresh cases of influenza placed in the isolation ward, and people were being urged to undertake in-home quarantine if in doubt. Approximately fifty people were undergoing mandated quarantine. It was also on this day that the virus would claim its second victim, 29-year-old George Slatyer. On April 29, the whole hospital was set aside for pneumonic influenza patients, and a temporary hospital set up in nearby St Saviours Church Hall. [13]

An all-too-frequent headline in Goulburn Evening Penny Post in the early parts of 1919.

By the time the emergency hospital was dismantled and the general wards of the hospital were reopened on the 9th of September, 1919, 42 people had died from pneumonic influenza.

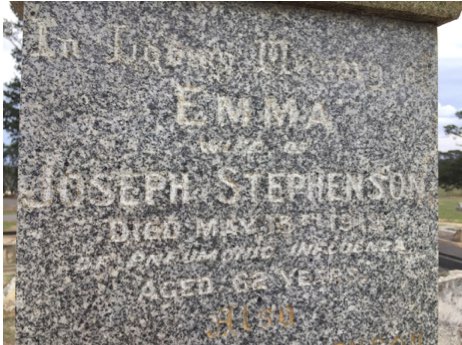

The headstone of Emma Stephenson. Goulburn man Joseph Stephenson lost his wife, daughter and son to the pneumonic influenza pandemic.

The effects of the pandemic lasted longer than the manifestation of symptoms. For years afterwards, news of a death from influenza was greeted with a sweeping fear in the community. While we had more time to prepare than most other regions due to our central location, we were not immune from its ravages.

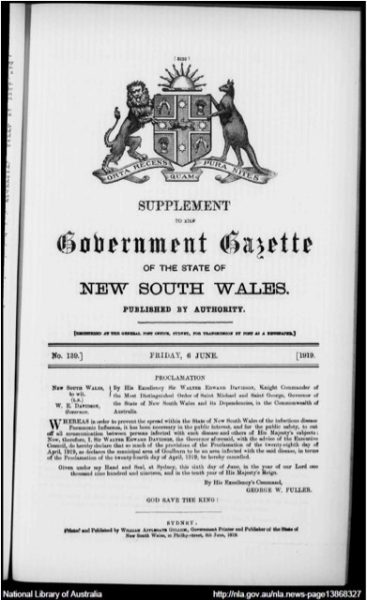

Cancellation of Infection Protocol for the Municipality of Goulburn, June 1919.

References:

[1] Peter Hobbins, Centenary of Spanish Flu Pandemic in Australia, created 21 January 2019, University of Sydney, <https://sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2019/01/21/centenary-of–spanish-flu–pandemic-in-australia.html>, accessed 23 April 2019.

[2] National Museum of Australia, Defining Moments: Influenza Pandemic, <https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/influenza-pandemic>, accessed 23 April 2019.

[3] NSW State Archives & Records, Pneumonic Influenza (Spanish Flu), 1919, <https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/stories/pneumonic-influenza-1919>, accessed 23 April 2019.

[4] National Museum of Australia, Defining Moments, <https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/influenza-pandemic>.

[5] NSW State Archives & Records, Pneumonic Influenza, <https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/stories/pneumonic-influenza-1919>.

[6] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 4 February 1919.

[7] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 4 February 1919.

[8] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 4 February 1919.

[9] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 1 April 1919.

[10] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 19 April 1919.

[11] J.M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History, Viking Penguin, 2004.

[12] Barry, The Great Influenza.

[13] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 20 May 1919.

[14] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 15 May 1919

[15] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 26 June 1919 and 4 September 1919.

[16] Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 27 January 1920.