Riot, Bets and Class

Cricket is now the prevailing amusement of the day. Let no man henceforth set up for a sporting character whose name is not enrolled among the ‘gentlemen cricketers’ of Sydney”[1] The Sydney Gazette, on the formation of a new cricket club, 1832.

Victorian gentility, civility, and sobriety. If there is ever an image to be conjured of early colonial cricket, it seems to be this one. [2] However, early colonial cricket in Sydney was coarse. Inter-colonial rivalry, gambling, drinking, and cheating were all commonplace. In retrospect, the Riot of 1879 is in keeping with Australian irreverence in being both utterly serious and farcical. February 8th, the day of the riot, underscores this perfectly. Not only are two prominent Australians directly involved in this match, no less than Edmund Barton as umpire and Banjo Patterson as rioter but it also was the same day that Ned Kelly dictated the Jerilderie Letter. In this essay, I will contextualise the Riot of 1879 and its aftermath, and through the lens of cricket challenge certainties of national and social cohesion.

‘No trifling degree of interest’

If there is one theme by which to measure colonial cricket in Sydney it is enthusiasm. Cricket was popular. The game was enjoyed by young and old and, unlike in England, it crossed broader class boundaries.[3] Yet, as the previous edition of Outside Off makes clear, despite some exceptions the game was at the apex of a British patriarchal society. The leisure by which to watch, play and earn from the game still had rigid boundaries. If it did not tightly constrain, it actively excluded those outside the ‘mainstream’. Women and people of colour were either ignored or omitted. [4] It is relevant to understand how this reflected the Australian society of the nineteenth century and how its legacy still informs our own. Societal leisure, like sport can seem removed but it is critical to understand that leisure is reflective of society and not separate to it.

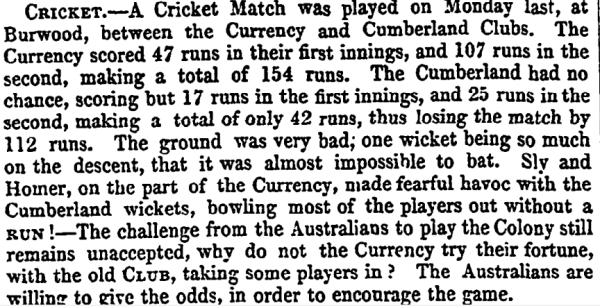

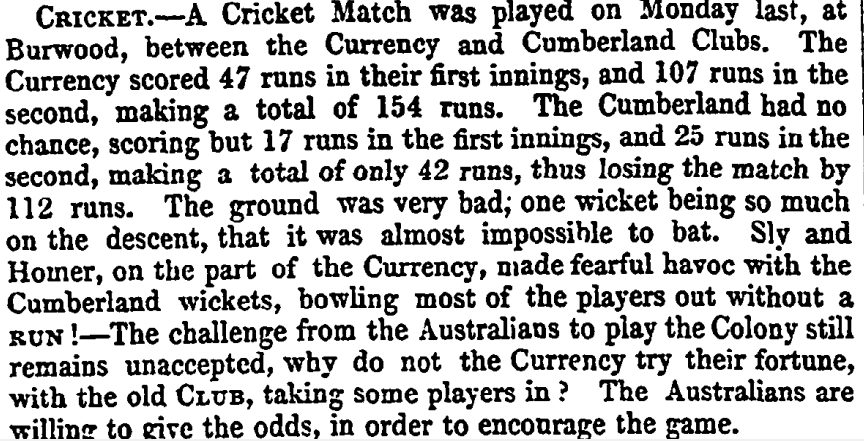

Where cricket existed there was rivalry. Where there was rivalry, there were bets. The Australian of the 1830s offers an insight into this curious relationship by declaring that cricket’s ‘noble English character’ was naturally free from ‘intemperance and gambling’. [5] Yet in 1836, J.R. Hardy as editor of the Australian and prominent cricketer himself, suggested the demolition of Cricket Grounds to precisely prevent such behaviour.[6] If gambling on cricket was prominent, then so was antagonism. Animosity between sporting groups is simple to foster but in Australia there seemed to be a special enthusiasm for cheating and underhanded tactics. Illegal bowling actions, condition of the wickets, the ball and even the length of matches all characterised early inter-colonial matches.[7] One match between the Currency and Cumberland (Parramatta) Clubs in 1845, which had 10 shillings per bat as prize money, was noted for a ball so soaked in oil that it had no elasticity and a wicket that sloped so far downward it was farcical. The Cumberland men expressed profound dissatisfaction.[8]

The Atlas, 25th January 1845. Note the ‘willingness to give odds’.

This was the society of cricket in Sydney, egalitarian if only in its sense to cheat and gamble equally. Cricket was not rarefied in the same way by the same people. It was this society that the English touring side of 1879, gentlemen most and professionals few, took guard.

However, for the Marylebone Cricket Club, cricket was not simply respected it was revered. If these early cricket matches between the Australian colonies and England reveal anything, is that this cultural exchange was from high status to low. Because cricket was viewed by many at the time as making the bonds of empire stronger, there is little doubt as to whom is owed fealty. Jared Van Duinen, cricket writer and sports historian, certainly views the decade before the Riot as a ‘high water mark of British race Imperialism’ in Australia.[9] Thus, the ensuing worsening of relations cannot be entirely a moment of proto-nationalism simply because frequent references to ‘British character’ and ‘British race’ are all in the fallout. Yet there is one stressor to this particular cultural exchange above most, both inside and outside of cricket – Class.

Throughout the tour and its aftermath, English class distinctions were asserted rigorously. For example, the ‘players’ (those that tried to make a living from the game), were sent to Australia on second class tickets and stayed at cost effective hotels having only been selected to do the strenuous fast bowling in the Australian heat.[10] The actual cost of the tour itself was at the behest of the Melbourne Cricket Club, who ‘hosted’. A stark contrast to the Australian Tour of England in 1878 where capital was raised as a joint stock venture, all players contributing £50 each with a 16-match preliminary tour.[11] The XI selected for this touring side were overwhelmingly from the upper classes and thus enjoyed significant support from their aristocratic peers. Oxbridge graduates, missionaries and peers all emphatically followed their progress. [12] English cricket’s cultural exchange was from a fundamentally conservative framework, a high-class social function both respected and revered. Low colonial frivolity would not break Faith with the Laws of the Game.

“I was surrounded by a howling mob”

–Fourth Lord Harris in a letter to a friend 11th February 1879.

The Riot itself like most controversies on a cricket field began with a disputed umpire’s decision. The star Australian batsman, Billy Murdoch, was judged by umpire George Coulthard to have been run out for 10 in New South Wales’ second innings reply to England’s total of 267. This decision was not received well by the crowd, the majority of whom had ignored signage about the illegality of betting and heavily backed a victory for NSW.[13] The crowd may have been further incensed by what it perceived to be bias from the umpire, Coulthard. Coulthard was no ordinary umpire. He was a star player for Carlton and a rising cricket talent for his home colony, Victoria. He further ‘endeared’ himself to the hearts of NSW by failing to give out to his employer, Lord Harris, who was caught behind during England’s first innings.[14] For giving Murdoch out and thus NSW’s only chance of saving the match, the pitch was invaded.

The Riot itself like most controversies on a cricket field began with a disputed umpire’s decision. The star Australian batsman, Billy Murdoch, was judged by umpire George Coulthard to have been run out for 10 in New South Wales’ second innings reply to England’s total of 267. This decision was not received well by the crowd, the majority of whom had ignored signage about the illegality of betting and heavily backed a victory for NSW.[13] The crowd may have been further incensed by what it perceived to be bias from the umpire, Coulthard. Coulthard was no ordinary umpire. He was a star player for Carlton and a rising cricket talent for his home colony, Victoria. He further ‘endeared’ himself to the hearts of NSW by failing to give out to his employer, Lord Harris, who was caught behind during England’s first innings.[14] For giving Murdoch out and thus NSW’s only chance of saving the match, the pitch was invaded.

Here follows much dispute about what happened next. Either Coulthard or Lord Harris were struck by rioters unknown. What is certain however is that an England player, Albert ‘Monkey’ Hornby had his shirt ripped whilst accosting a pitch invader.[15] Notably, umpire Barton agreed with his counterpart in both decisions.

Play was halted. When play resumed on Monday, NSW eventually lost by an innings and 41 runs.

The aftermath was fierce. Letters, accusations, rebuttals filled newspaper columns. Some from the crowd accused the England players of calling them ‘sons of low convicts’.[16] In response to this accusation and others, Lord Harris penned a letter. In this letter, he vociferously denied all suspicions that umpire Coulthard had bet on the match, that any of his team had behaved poorly and lay blame squarely on the crowd, for illegal betting. [17] This was not received well in NSW. The response is best evidenced by the New South Wales Cricket Association. A letter, appearing in The Argus, the Sydney Echo and the Mercury was unequivocal.

“The country upon which such reproach could be fastened would be unworthy of a place among civilized communities, and in the imputation is especially odious to Australians who claim to have maintained the manly, generous and hospitable characteristics of the British race.” [18]

Insults to perceived ‘British racial characteristics’ may invite parallels to American revolutionary language around ‘British rights’ but direct comparison distorts the unique Australian context. This war of words about cricket demonstrates a nuance of an ‘Australian’ identity masked by the very things so intolerable to the class lens of English society. Cricket through its own eccentricities is self-defeating. Fundamentally a conservative construct, to nurture hegemonies ensures precisely the opposite; idiosyncrasy, agency, and character. The Riot of 1879 is one moment among many that illuminates this.

References:

Jack Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket (Ringwood, Victoria: Viking, 1992).

Jared Van Duinen, The British World and an Australian National Identity; Anglo-Australian Cricket, 1860-1901 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Phillip Derriman and Pat Mullins, Bat & Pad: Writings on Australian Cricket 1804-2001 (Marrickville: Australian Consumers Association, 2001).

Anthony Bateman, Cricket, Literature and Culture: Symbolising the Nation, Destabilising Empire (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2009).

“Lord Harris and the Sydney Disturbance”. The Mercury, 12th June 1879. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8977850

Stephen Wagg, ed., Cricket and National Identity in the postcolonial age; Following On (London UK, Routledge, 2005).

Jas Scott, edited by Richard Cashman & Stephen Gibbs, Early Cricket in Sydney 1803-1856 (Sydney: New South Wales Cricket Association, 1991).

New South Wales Cricket Association, “Lord Harris and the Sydney Cricketers” The Argus, 9th June 1879. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5946279

[1] Derriman and Mullins, Bat & Pad, p. 13.

[2] Bateman, Cricket, Literature and Culture, p. 1.

[3] Scott, Cashman and Gibbs, Early Cricket in Sydney 1803-1856, pp. xii-xiii.

[4] Wagg, Cricket and National Identity in the postcolonial age, p. 9.

[5] Scott, Cashman and Gibbs, Early Cricket in Sydney 1803-1856, p. 34.

[6] Scott, Cashman and Gibbs, Early Cricket in Sydney 1803-1856, p. 53.

[7] Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, pp. 4-5.

[8] Scott, Cashman and Gibbs, Early Cricket in Sydney 1803-1856, p. 117.

[9] Van Duinen, The British World and an Australian National Identity, p. 21.

[10] Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, p. 52.

[11] Van Duinen, The British World and an Australian National Identity, p. 31.

[12] Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, p. 53.

[13] Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, p. 55.

[14] Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, p. 55.

[15] Pollard, The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, p. 55.

[16] Van Duinen, The British World and an Australian National Identity, p. 33.

[17] ‘Lord Harris and the Sydney Disturbance’. The Mercury 12th January 1879. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/8977850

[18] New South Wales Cricket Association, “Lord Harris and the Sydney Cricketers” The Argus, 9th June 1879. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5946279

0 Comments