Written by Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Volunteer

To celebrate Women’s History Month in 2022, the Royal Australian Historical Society will continue our work from previous years to highlight Australian women that have contributed to our history in various and meaningful ways. You can browse the women featured on our webpage, Women’s History Month.

Botanical artist, anthropologist, and Aboriginal rights activist Olive Muriel Pink lived a long and fascinating life that took her from her birthplace in Hobart all the way to Alice Springs. Today she is remembered as a controversial, even eccentric, figure in outback Australia during the twentieth century.

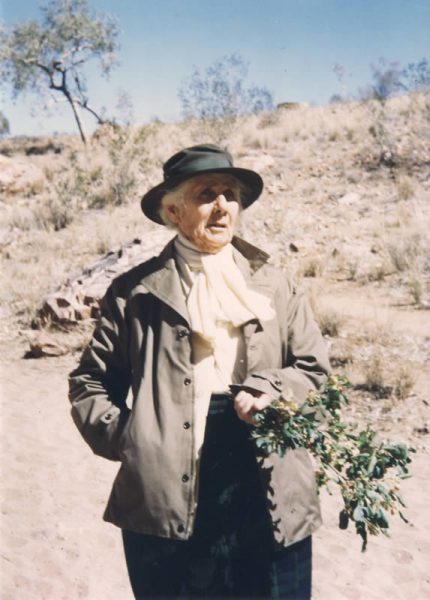

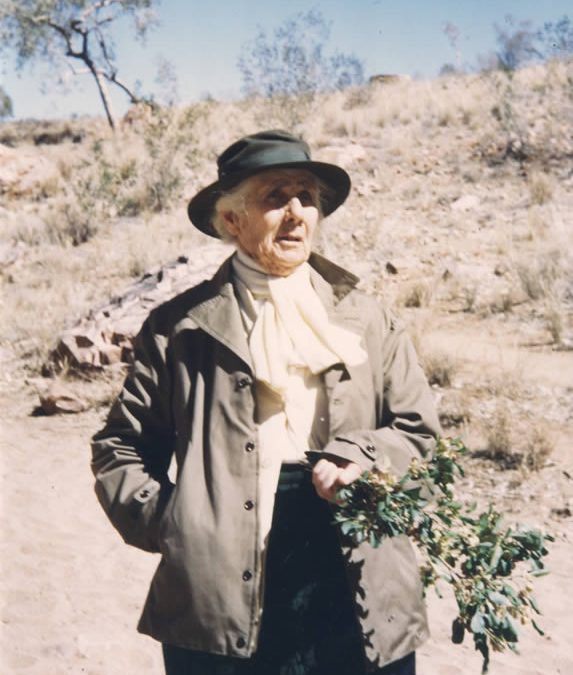

OLIVE PINK IN HER GARDEN, UNDATED. IMAGE COURTESY OLIVE PINK BOTANIC GARDEN COLLECTION.

Born in 1884 in Hobart, Tasmania, Olive showed a keen interest in both arts and the environment from a young age. A friend of her father, A. T. Bell, gifted Olive A Handbook of the Plants of Tasmania in 1896, when she was twelve years old. Olive kept it with her the rest of her life. [1] She was similarly enchanted by her grandmother’s garden in Hobart, commenting on the abelia from the Himalayas, peonies from China, forget-me-not from the Alps, and tulips—her “favouritest” flower—from Turkey: “One’s garden would seem like travelling over the world!” [2]

Olive studied then taught art at Hobart Technical School before moving to Perth, then Sydney, with her mother. She worked for the Red Cross during the war while studying at Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School, and in 1915 was employed as a tracer by NSW Government Railways and Tramways. Olive painted excursion posters and other graphics for the department until her retrenchment during the Great Depression. [3]

Olive had taken a trip to Ooldea in South Australia in 1926-27 to visit her friend Daisy Bates—at the time, a prominent anthropologist and welfare worker among the First Nations people there. On the train between Ooldea and Alice Springs, Olive “sketched flowers wherever railway workers reported them”. These 64 sketches are now held by the University of Tasmania. It was on this journey that Olive first became interested in the rights and welfare of Aboriginal people. [4]

This was an interest, and later a passion, that would dictate the rest of her life. Olive took courses in anthropology at the University of Sydney and received government grants in the 1930s to study the eastern Arrente of Alice Springs and Warlpiri of the Tanami region in the Northern Territory. Her decision not to publish her Warlpiri research out of respect for the secret rituals it relied upon effectively ended her anthropological career. [5] Some commentators have, however, critiqued the fact that she chose to publish two papers on the Arrente, despite similar secret knowledge disclosed. [6]

Olive returned to Alice Springs in 1942, seeking to establish a “secular sanctuary” for the Warlpiri. From 1946 she lived with some Warlpiri people for a time, before returning to Alice Springs to work as a cleaner at the courthouse, where she closely monitored how Aboriginal defendants were treated. This did not endear her to the local population. Unsuccessful in her petition for land for a museum, Olive turned part of her hut into a gallery, where luminaries such as Sidney Nolan visited, until trouble stirred with the locals and it was burned down. [7]

In 1956, Olive was finally granted land to establish the Australian Arid Regions Native Flora Reserve with the help of her gardener Johnny Jambijimba Yannarilyi, where she lived for the last twenty years of her life. Upon her death in 1975 it was renamed the Olive Pink Botanic Garden, and opened to the public in 1985. Today it contains over six hundred Central Australian plant species, forty of which are rare or threatened. [8]

“It was worth fighting for—to live at this site,” Olive wrote in 1959. “One looks at Mt Gillen—and the Todd ‘River’ Gums … I thought it so ‘heavenly’ a view.” She was buried at Alice Springs with her gravestone facing west, overlooking that very view. [9]

References:

[1] Gillian Ward, ‘Olive Pink as artist – a remarkable Tasmanian’, paper presented at a meeting of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 8 April 2014, in Papers and Proceedings 62, no. 1 (March 2015), p. 20.

[2] Olive Pink, quoted by Colleen O’Malley in Kieran Finnane, ‘A life in flowers: new account of the extraordinary Olive Pink’, Alice Springs News vol. 25, no. 3, May 2018, https://alicespringsnews.com.au/2018/05/08/a-life-in-flowers-new-account-of-the-extraordinary-olive-pink/.

[3] Julie Marcus, ‘Pink, Olive Muriel (1884–1975)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/pink-olive-muriel-11428/text20365, accessed 4 March 2022.

[4] Marcus, ‘Pink, Olive Muriel’; ‘Communities Tasmania – Olive Pink’, Department of Communities Tasmania, accessed 6 March 2022, https://www.communities.tas.gov.au/csr/information_and_resources/significant_tasmanian_women/significant_tasmanian_women_-_research_listing/olive_pink.

[5] Marcus, ‘Pink, Olive Muriel’.

[6] Janet McCalman, ‘Review of The Indomitable Miss Pink: A Life in Anthropology, by J. Marcus’, Isis vol. 95, no. 2 (2004), p. 329.

[7] Marcus, ‘Pink, Olive Muriel’.

[8] Marcus, ‘Pink, Olive Muriel’; Angela Heathcote, ‘Olive Pink is Australia’s very own Georgia O’Keeffe’, Australian Geographic, 30 November 2018.

[9] Olive Pink, letter to Dr William Crowther, 2 October 1959, quoted in Ward, ‘Olive Pink as artist’, p. 31-32.

0 Comments