Written by Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Intern

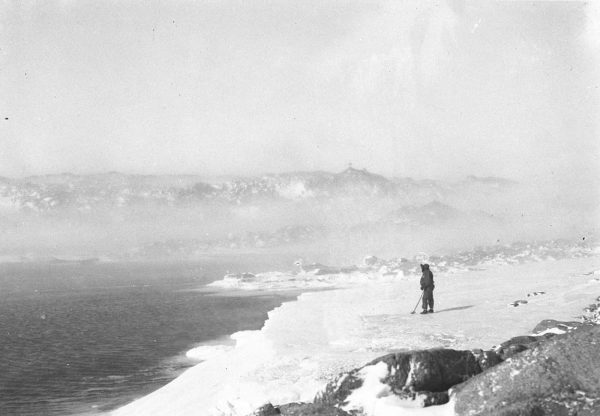

CONTEMPLATION: XAVIER MERTZ LOOKS OUT OVER THE BOAT HARBOUR AT CAPE DENISON, 1912. DRIFTING SNOW MAKES THE LANDSCAPE LOOK FUZZY. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRANK HURLEY. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

110 years ago in 1911, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) set sail from Hobart, Tasmania, on the old whaling ship Aurora. Among the crew were a young Frank Hurley, soon-to-be war photographer; Frank Wild, English explorer and Antarctic veteran; Belgrave Ninnis, son of the Arctic explorer of the same name and lieutenant with the Royal Fusiliers; Xavier Mertz, Swiss champion skier; and Douglas Mawson, Australian geologist and leader of the expedition, six months shy of his thirtieth birthday on the day of the Aurora’s embarkation.

Over the course of their three-year journey, the AAE returned some of the most remarkable scientific finds of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, including the first meteorite discovered in Antarctica. The data from the expedition took thirty years to be published in its entirety. By the end of his Antarctic career, Mawson would claim forty-two percent of the continent for Australia—a figure which stands today. But Mawson and the AAE are best remembered for achievements of a different kind: those of endurance, and survival against all odds, in what has been called by some ‘the most terrible polar exploration ever’. [1]

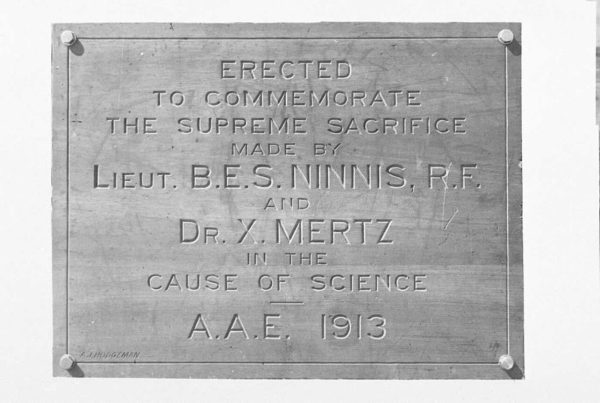

Last month, on 25 May 2021, three new memorial plaques were unveiled at Mawson Place, Hobart Harbour, 150 metres from where the AAE first set sail. Dedicated to the lives lost on that fateful expedition, the ceremony was attended by British High Commissioner to Australia Victoria Treadell and Swiss Ambassador Pedro Zwahlen. ‘Recognition of the sacrifices of this expedition has been long overdue’, David Jensen, founder of the Mawson’s Hut Foundation, remarked in his opening speech. [2]

Previously, the only monument to honour the fallen polar heroes was a single wooden cross erected at Cape Denison, East Antarctica, the home base of the AAE and ‘at its worst … one of the most terrible environments on earth’. [3] Beset by brutal katabatic winds, hundreds of kilometres from the next outpost, very few people outside scientific circles make the trek to the memorial.

It is about time they were commemorated on Australian soil.

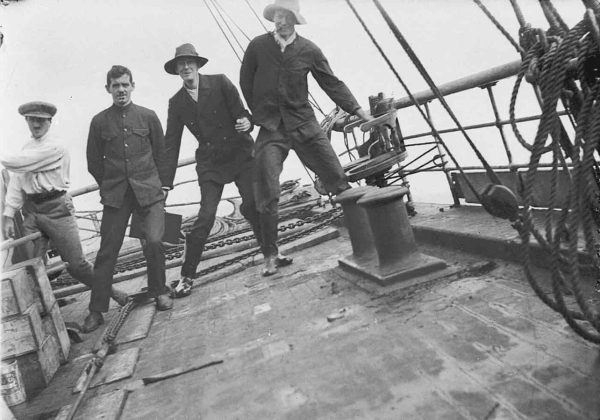

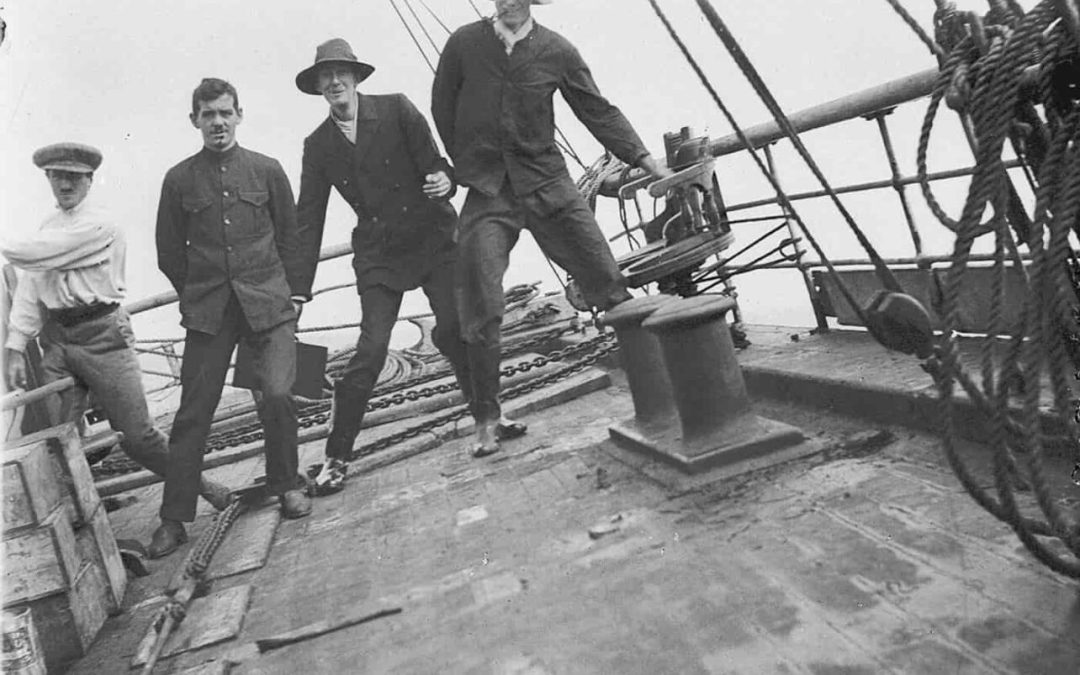

HAPPIER TIMES: FROM L TO R MERTZ, SECOND ENGINEER CORNER, SECOND OFFICER PERCY GRAY, AND NINNIS, EN ROUTE TO AUSTRALIA ON BOARD THE AURORA, 1911. PHOTOGRAPH BY AURORA’S CHIEF ENGINEER F. J. GILLIES. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

‘A man of character, generous and of noble parts’. ‘A fine fellow and a born soldier’. So Douglas Mawson described his companions Xavier Mertz and Belgrave Ninnis in his published account of the expedition, Home of the Blizzard. [4] The three men set out from Cape Denison on 10 November 1912 as the Far Eastern Party, one of several smaller expeditions to explore the uncharted polar territory. With them went seventeen sledging dogs. They made good pace for over a month, travelling 500 kilometres from base camp across glaciers pitted with hidden crevasses.

On 13 December the men made camp, and redistributed their supplies from three sledges to two. The next day began as normal, Mertz skiing ahead, Mawson following, standing on the runners of his sled, Ninnis jogging beside his and bringing up the rear. Mertz spotted a crevasse. He halted and raised his ski pole to alert the others. He and Mawson passed over without incident. Then Mertz halted again, alarmed. Mawson looked back. Ninnis was not behind them.

The two retraced their footsteps, frantic, hoping Ninnis was simply out of sight behind a rise in the snow. They found the crevasse instead, its snow cover fallen through. Crawling forward on his stomach, peering into the darkness, Mawson saw two dogs lying on a ledge far below: one dead, the other badly injured and whining. They had fallen through the snow bridge without a sound, along with the expedition’s other best dogs, most of the food and supplies, and their master, Lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis. [5]

Mawson and Mertz called for Ninnis for hours. The rope they carried was not long enough to reach the ledge where the dogs were, let alone deeper into the crevasse. Shock soon gave way to grief: ‘Our fellow, comrade, chum, in a woeful instant, buried in the bowels of that awful glacier’, Mawson later wrote. [6] In his diary, Mertz was numb: ‘We could do nothing, really nothing. We were standing, helplessly, next to a friend’s grave, my best friend of the whole expedition’. [7]

In redistributing the supplies the previous night, Mawson had thought the first sled would be the one to encounter any difficulty, so kept essential supplies to a minimum and hitched it to the weakest dogs. He and Mertz now faced a thirty-day return journey with ten days’ worth of food, minimal supplies, no dog food and no tent. Mawson’s diary captures the bleak situation: ‘May God help us’, he wrote. [8]

Belgrave Edward Sutton Ninnis was twenty-five when he died. Responding to an advertisement placed by Mawson about the expedition in London, Ninnis was hired as the minder of the fifty sledging dogs Mawson purchased from Greenland. Ninnis had no experience in dogs or polar exploration, but his military rank and family history—his father, also Belgrave Ninnis, was a prominent Arctic explorer—likely influenced Mawson’s decision to recruit the young lieutenant. [9]

Mertz also joined the expedition in London and was appointed to the dogs with Ninnis. Only five years older than the lieutenant, the two soon became close friends. Today the Mertz and Ninnis Glaciers sit side-by-side on the Antarctic coast.

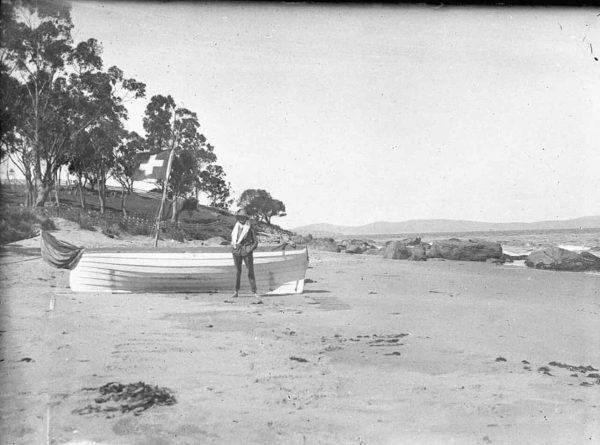

PHOTOSHOOT: NINNIS AT THE DOG QUARANTINE STATION ON THE DERWENT RIVER, 1911, BEFORE THE EXPEDITION EMBARKED. PHOTOGRAPH BY HIS FRIEND XAVIER MERTZ. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

MEN AT WORK: NINNIS (FOREGROUND) IN THE CATACOMBS LEADING TO THE CAPE DENISON HUT, 1912. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRANK HURLEY. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

Mawson and Mertz made the decision to retrace their steps across the glacier back to camp, rather than attempt a longer route via the coast. They returned to their camp from the previous night, where they cut poles from the abandoned sledge to create a makeshift canvas tent.

The two men travelled 320 kilometres of the 500 kilometre journey together. Their daily rations were a mere 400 grams, compared to the usual 960, even supplemented by the meat from their remaining dogs—a necessity that was likely traumatising for Mertz especially, who had been entrusted with their care. Already stricken with grief, both men soon fell sick as well. Their skin and hair began to fall off; they suffered abdominal pain, weight loss, and dizziness, alongside the snow-blindness Mawson was already experiencing. The last dog, Ginger, died on 28 December. In the new year, Mertz’s condition declined rapidly. He had fever, fits, and bouts of dysentery, and died ‘peacefully at about 2 am’ on 8 January 1913. [10]

Mawson was now alone, ‘on the wide shores of the world’. [11]

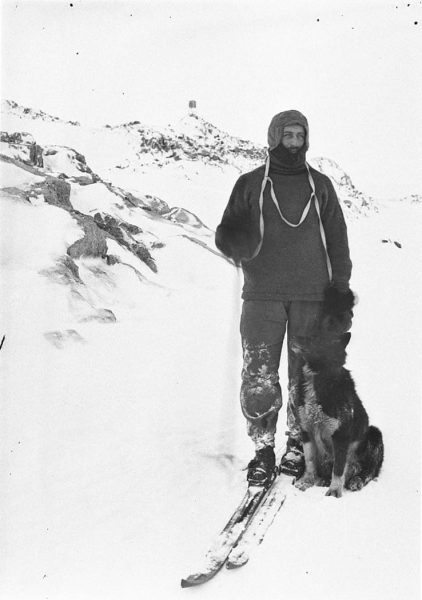

MAN’S BEST FRIEND: MERTZ AND ONE OF HIS FAVOURITE DOGS, BASILISK, 1912. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRANK HURLEY. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

Dr Xavier Mertz was twenty-eight when he joined the AAE. He had a doctorate in law, was a national ski champion in his native Switzerland, and an experienced mountaineer. On board the Aurora from London to Australia, he dabbled in his hobby of amateur photography, setting up a makeshift darkroom in the bowels of the ship.

The only non-British European to join Mawson’s expedition, Mertz was a novelty for many of the men. His imperfect English and habit of yodelling whenever the mood struck both amused and bemused his companions. In her paper on Mertz in Hobart, Anna Lucas wryly describes Mertz as ‘Ever the patriot, he also wrote that he was taking the Swiss flag with him, intending to raise it at several places on the Antarctic continent (which he did)’. [12]

Mawson did not expect to survive the final leg of the journey back to base. But he was determined to travel as far as he could so his body, and his and Mertz’s diaries, could be found. ‘How short a distance it would seem to the vigorous’, Mawson wrote, no doubt remembering the easy trek he, Mertz, and Ninnis had undertaken two months ago, ‘but what a lengthy journey for the weak and famished!’ [13]

The soles of his feet had peeled off completely. Mawson smothered them in lanolin and bandaged the skin back on, but the pain made the miles twice as hard, and twice as slow, to cover. On 17 January he fell into a crevasse, saved only from Ninnis’ fate by his sledge getting stuck in a snowdrift. Mawson, at this point weighing little more than fifty kilograms, pulled himself up by his rope, hand over bloodied hand.

On 29 January at approximately two p.m., twenty-one days after Mertz’s death, Mawson spotted a cairn with a store of food inside and a note, directing him to the supply cache thirty miles from base camp. The note had been written at eight a.m. that day: Mawson had missed his companions by mere hours.

Three days later he reached the cache of Aladdin’s Cave. Inside were three oranges and a pineapple: Mawson wept, ‘overcome, he later said, by the sight of something that was not white’. [14]

A blizzard kept Mawson inside the cave for the next five days. On 8 February, three months after setting out from Cape Denison with Ninnis and Mertz, Mawson made it back. In the distance of Commonwealth Bay he could make out the distinct shape of the Aurora, departing base camp at last after already delaying almost a month in the hope of the Far Eastern Party’s return.

But all, for Mawson, was not lost. Six men had stayed behind, willing to brave another Antarctic winter to search for their lost companions: Bob Bage, Francis Bickerton, Alfred Hodgeman, Sidney Jeffyres, Cecil Madigan, and Archibald McLean. Mawson could scarcely believe it: ‘They seemed almost unreal—I was in a dream’. [15]

The AAE was the first expedition in the world to establish long-term wireless radio contact with mainland Australia. Mawson used it to send a message to his fiancée, Paquita, in those long months before the Aurora could return through the ice: ‘Deeply regret delay. Only just managed to reach hut. Effects now gone but lost most of my hair. You are free to consider your contract but trust you will not abandon your second hand Douglas’.

Paquita replied: ‘Deeply thankful you are safe. Warmest welcome awaiting your hairless return’. [16]

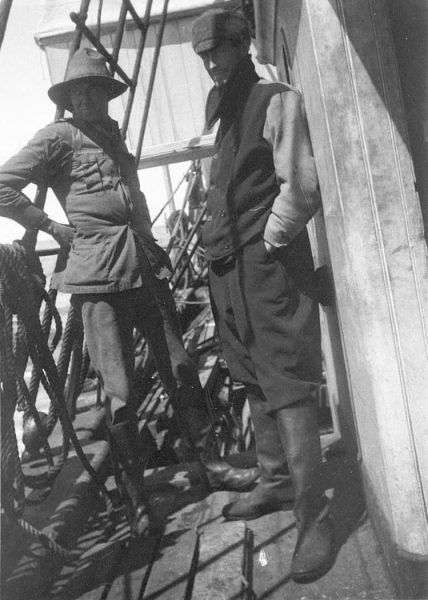

ON DECK: NINNIS AND MAWSON ON BOARD THE AURORA, 1911. PHOTOGRAPH BY PERCY GRAY. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

AT REST: MAWSON RESTING BY HIS SLEDGE, MARCH 1912. PHOTOGRAPH BY XAVIER MERTZ. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

Tramping over the plateau, where reigns the desolation of the outer worlds, in solitude at once ominous and weird, one is free to roam in imagination … One is in the midst of infinities—the infinity of the dazzling white plateau, the infinity of the dome above, the infinity of the time past since these things had birth, and the infinity of the time to come … [17]

So wrote Mawson in Home of the Blizzard. Despite the tragedy he had endured in the Antarctic, he was never in doubt, and remained forever in awe, of its beauty. He would return to Antarctica as leader of the British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition in 1929.

Most of the AAE went on to fight in World War I. Some, including Bage and McLean, lost their lives. Perhaps, had he survived Antarctica, Belgrave Ninnis would have joined them. Switzerland was a neutral country in the war, but Xavier Mertz had already proven himself an adventurer. What choices would he have made, given time?

We now know that the illness both Mawson and Mertz suffered from after the death of Ninnis was hypervitaminosis A, an excess of vitamin A in the body. Husky livers contain toxic levels of the vitamin, and were consumed by both men over several weeks. Mertz, used to eating less meat than Mawson, and especially once in a weakened state, may have been given the palatable liver over the rest of the ‘stringy’ dog meat, thus explaining his rapid decline. [18]

We also know that Ninnis’ habit of running alongside his sledge cost him his life. Mertz and Mawson passed over the snow cover of the crevasse without incident, their weight distributed on skis and sled runners respectively. Ninnis’ weight was concentrated in a very small area, enough to break through the snow entirely. Some historians have criticised Mawson, arguing that as leader he should have insisted on skis for his men. [19]

But hindsight is easy, especially from the warmth, comfort, and solid ground of our own homes.

British explorer Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition of 1912 similarly ended in tragedy. Scott and his four companions set out to be the first to reach the South Pole but were beaten by a Norwegian team by little more than a month. All five men died on the return journey.

David Shearman, writing in 1978, compared the two terrible expeditions. ‘Scott’, he writes, ‘was defeated in his prime aim, which must have affected the high morale necessary to keep going. Mawson, on the other hand, was a scientist and he drove himself to deliver his wealth of scientific observations’. [20]

He succeeded. Yet it was not only scientific discovery Mawson brought back to Australia but a deeply tragic, and a deeply human, story of survival. Not only of himself, but of the memory of Ninnis and Mertz: two young, brave, adventurous, affable, devoted, capable men. Frozen in time, in photographs, in history, and forever on ice.

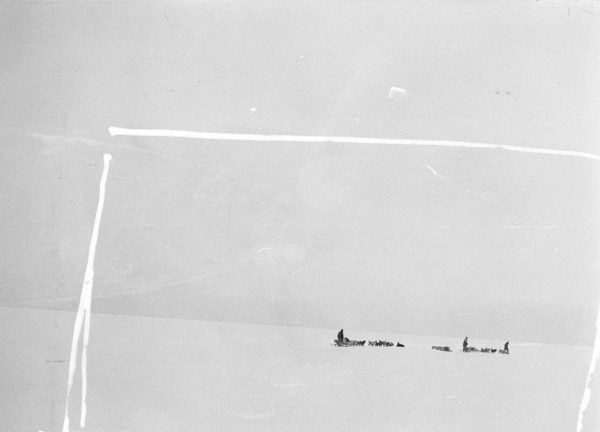

FAREWELLS: THE FAR EASTERN PARTY DEPARTING, NOVEMBER 1912. IT IS THE LAST PHOTOGRAPH OF MAWSON, MERTZ, AND NINNIS TOGETHER. PHOTOGRAPH BY ARCHIBALD MCLEAN. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

IN MEMORIAM: INSCRIPTION ON THE TABLET BELOW THE MEMORIAL CROSS FOR MERTZ AND NINNIS AT CAPE DENISON. PHOTOGRAPH BY FRANK HURLEY. IMAGE COURTESY MITCHELL LIBRARY, SLNSW.

References:

[1] Mike Dash, ‘The Most Terrible Polar Exploration Ever: Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic Journey’, Smithsonian Magazine, 27 Jan 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-most-terrible-polar-exploration-ever-douglas-mawsons-antarctic-journey-82192685/; ‘Mawson in the Antarctic’, National Museum of Australia, accessed 24 May 2021, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/mawson-in-the-antarctic.

[2] Dr Michael Wenger, ‘Great honour for first Swiss in Antarctica’, Polar Journal, 26 May 2021, https://polarjournal.ch/en/2021/05/26/great-honour-for-the-first-swiss-in-antarctica/.

[3] Alexandra Alvaro, ‘Memorial to honour Mawson’s ill-fated Far Eastern Party’s Antarctic voyage’, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 25 May 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-25/mawson-ill-fated-far-eastern-partys-antarctic-voyage-memorial/100161834; David Killick, ‘Life and death in the Home of the Blizzard’, Australian Antarctic Magazine, 23 May 2012, https://www.antarctica.gov.au/magazine/issue-22-2012/exploration/life-and-death-in-the-home-of-the-blizzard/.

[4] Sir Douglas Mawson, The Home of the Blizzard: Being the Story of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914 (London: W. Heinemann, 1915).

[5] Dash, ‘Polar Exploration’; Killick, ‘Life and death’.

[6] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard.

[7] ‘Mawson in the Antarctic’, NMA.

[8] Dash, ‘Polar Exploration’; Killick, ‘Life and death’.

[9] Wenger, ‘Great honour’.

[10] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard; Dash, ‘Polar Exploration’; Killick, ‘Life and death’; Douglas Mawson, with Fred Jacka and Eleanor Jacka, eds., Mawson’s Antarctic diaries (North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1988); Elizabeth Leane and Helen Tiffin, ‘Dogs, Meat and Douglas Mawson’, Australian Humanities Review no. 51 (Nov 2011): 1; David J. C. Shearman, ‘Vitamin A and Sir Douglas Mawson’, British Medical Journal 1 (Feb 1978): 283-285.

[11] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard.

[12] Anna Lucas, ‘Mertz in Hobart: Impressions of one of Mawson’s men while preparing for Antarctic adventure’, Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 146 (2012): 37-44.

[13] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard; Killick, ‘Life and death’; Shearman, ‘Vitamin A’.

[14] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard; Dash, ‘Polar Exploration’; Killick, ‘Life and death’; Shearman, ‘Vitamin A’.

[15] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard.

[16] Killick, ‘Life and death’.

[17] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard.

[18] Dash, ‘Polar Exploration’; Shearman, ‘Vitamin A’.

[19] Mawson, Home of the Blizzard; Dash, ‘Polar Exploration’.

[20] Shearman, ‘Vitamin A’.

0 Comments