Written by Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Volunteer

To celebrate Women’s History Month in 2022, the Royal Australian Historical Society will continue our work from previous years to highlight Australian women that have contributed to our history in various and meaningful ways. You can browse the women featured on our webpage, Women’s History Month.

In the early 2000s, the Australian Film Institute (AFI) Awards—now known as the AACTAs—tried out the nickname “the Lovelys”, in the style of the Oscars. The name did not last long. The woman they were named after, however, did: Louise Lovely, Australia’s first film star, with a career on stage and screen spanning twenty tumultuous years. [1]

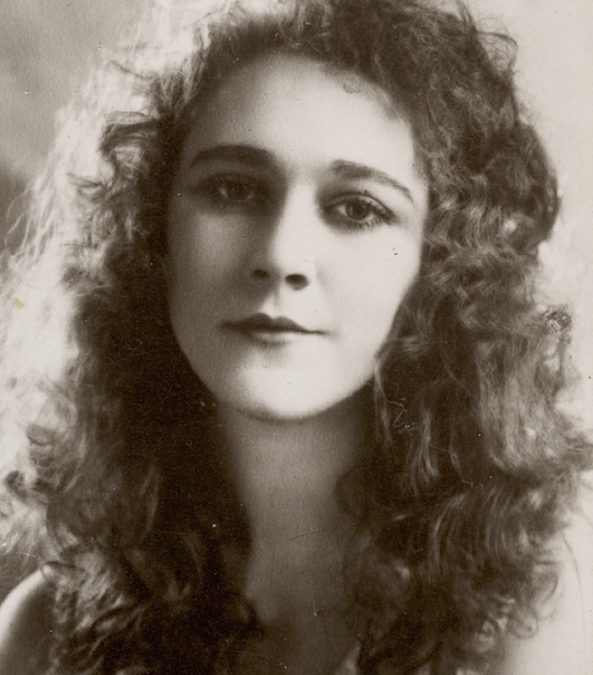

FOX FILMS PORTRAIT, CIRCA 1920S. IMAGE COURTESY NATIONAL FILM AND SOUND ARCHIVE, NFSA TITLE: 759526

Born in Paddington in 1895 to Swiss actress and singer Elise Lehmann, Louise enjoyed a life in the limelight from an early age. When she was nine she starred as Eva in a stage production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin under the name Louise Carbasse. From there, Louise appeared in several stage and low budget screen productions across Australia and New Zealand until her marriage to writer and fellow actor Wilton Welch in 1912, at age sixteen. The couple left Australia for America in 1914. [2]

Louise hit her stride in Hollywood. Signed to Universal Studios’ Bluebird Photoplays, Louise was also given a new look along with a new name. Her soon-to-be trademark golden ringlets were likely modelled after American film star Mary Pickford, symbolising Louise’s youth and innocence. [3] Her new name, Louise Lovely, was rumoured to have been given to her by Universal owner Carl Laemmle who exclaimed, upon seeing her screen test: “She’s lovely in herself and her work. Call her Louise Lovely.” [4]

In reality, the new name was likely part of her deal with Universal. It harnessed the “star system” that was beginning to filter from the stage to the screen. The importance of studio brand names for advertising film decreased, while the names of their stars increased—almost becoming brand names themselves. A Louise Lovely film advertised the type of role Louise would be playing—the innocent, naïve heroine—as well as the protective male hero cast opposite. [5]

Louise went on to make 24 films with Universal. Her departure from the studio involved a legal dispute over the use of her screen name, which effectively blacklisted her from Hollywood for most of 1918. She later signed with Fox to make a series of westerns with co-star William Farnum. In the post-war world, however, his “blue-collar burliness” and her golden-haired naivete were rapidly overshadowed by the audience’s desire for “sleek” masculinity and sophisticated women. [6]

Seeking to rejuvenate her career, in 1922 Louise and her husband toured America with A Day at the Studio, a vaudeville production requiring audience participation to demonstrate how films were made. In 1924 the couple brought the show home to Australia, where Louise was then engaged by writer Marie Bjelke-Petersen to produce a film version of her book Jewelled Nights. Louise produced and starred in the movie, which opened to Melbourne audiences on 24 October 1925 to great commercial success—though not enough to recoup the £8000 cost of making the film. [7]

Two years later, Louise testified to a royal commission into the Australian film industry, stressing the need for greater local support in order to compete against both the quality and quantity of imported films. She was not successful. Jewelled Nights was the final film Louise ever made. [8]

Louise lived the rest of her life quietly. She divorced Welch and married her second husband, Bert Cowen, in November 1928. The couple later settled in Hobart, where Bert managed the Prince of Wales Theatre and Louise the sweet shop next door. Interviewed in 1969, Louise quipped:

“These days, I usually hide behind my glasses … but people often say to me, ‘Aren’t you Louise Lovely?’” [9]

She died in 1980, Australia’s first, forgotten, film star.

References:

[1] Garry Maddox, ‘And the award for re-invention goes to…’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August 2011, https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/and-the-award-for-reinvention-goes-to-8230-20110818-1izye.html.

[2] Ina Bertrand, ‘Lovely, Louise Nellie (1895–1980)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 13 March 2022, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lovely-louise-nellie-7248; ‘Communities Tasmania – Louise Lovely’, Department of Communities Tasmania, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.communities.tas.gov.au/csr/information_and_resources/significant_tasmanian_women/significant_tasmanian_women_-_research_listing/louise_lovely.

[3] Jeanette Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, Australia’s Silent Film Festival, accessed 13 March 2022, http://www.ozsilentfilmfestival.com.au/index.php/louise-lovely/.

[4] Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, Australia’s Silent Film Festival; Jeannette Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely, Bluebird Photoplays, and the Star System’, The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 4, no. 2 (Fall 2004), pp. 71-72; Jeannette Delamoir, ‘Styling a star: “Call her Louise Lovely”’, Journal of Australian Studies 22, no. 58 (1998), p 52; Jenny Gall, ‘Fan mail and photos of a silent film star’, National Film and Sound Archive, accessed 13 March 2022, https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/louise-lovely-fan-mail.

[5] Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, The Moving Image, pp. 67, 72; Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, Australia’s Silent Film Festival; Delamoir, ‘Styling a star’, pp. 48, 50-51.

[6] ‘Communities Tasmania – Louise Lovely’; Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, The Moving Image, p. 77; Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, Australia’s Silent Film Festival.

[7] ‘Communities Tasmania – Louise Lovely’; Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, Australia’s Silent Film Festival; Bertrand, ‘Lovely, Louise Nellie’.

[8] Bertrand, ‘Lovely, Louise Nellie’.

[9] Delamoir, ‘Louise Lovely’, The Moving Image, p. 72.

0 Comments