By Davina Jackson [PhD, M.Arch, FRGS, FRSA, FRSN]

Two hundred years ago, in June 1821, Australia’s first learned society was launched in Sydney. Named the Philosophical Society of Australasia – because ‘natural philosophy’ was the prevalent term for science at that time – the group comprised seven prominent men who shared the goal of establishing a museum of natural history.

PORTRAIT OF JUDGE BARRON FIELD, PAINTED IN THE EARLY 1820S, WHEN HE WAS A FOUNDER OF THE PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALASIA [MITCHELL LIBRARY, STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES]

The founders were Judge Barron Field, Dr Henry Grattan Douglass, Colonial Secretary Frederick Goulburn, surveyor John Oxley, merchant Edward Wollstonecraft, Captain John Irvine and Hawkesbury landowner John Bowman. They elected as their president Sir Thomas Brisbane, the Governor, who was a passionate astronomer.

Although the Philosophical Society only held a few meetings, it began a lineage of scholarly fellowships that solidified in 1866 when Queen Victoria formally signed assent to The Royal Society of New South Wales (RSNSW). It was incorporated by an Act of the NSW Parliament passed in 1881.

In 2021 and 2022, the RSNSW is highlighting the history of NSW intellectual societies with an exhibition, Nexus, in the Jean Garling Room of the State Library of NSW. It can be visited (during limited hours) after the library reopens.

The RSNSW also has compiled Australia’s first author-alphabetical and chronological bibliography of key science papers published between 1821 and Australia’s Federation in January 1901. This list cites chapters from Barron Field’s 1822 science anthology, Geographical Memoirs of New South Wales, and includes hotlinks to online facsimiles of 635 papers by 171 authors that were published in 35 editions of the RSNSW’s annual Journal and Proceedings.

The JProc papers especially illuminate the culture of research, thrusts of discovery, and relations among leading scientists during the New South Wales colony’s gold boom decades.

By far the most prolific essayist was the Sydney Observatory-based astronomer and meteorologist Henry Chamberlain Russell, who published 91 papers in volumes 3-35, including annual rainfall maps and monthly weather observations taken atop Observatory Hill. He also analysed floods of the Darling River and Lake George, how rain evaporated from paddocks, and telescope views of astronomical phenomena, including double stars and Transits of Venus, Mars and Saturn.

DRAWING OF SYDNEY OBSERVATORY, SKETCHED IN 1858 [MUSEUM OF APPLIED ARTS AND SCIENCES]

Another prominent writer was the University of Sydney’s Professor of Geology and Mineralogy, Archibald Liversidge, who wrote four papers on NSW minerals and meteorites in the annual Transactions of the RSNSW, before he began to edit the publication in 1875 and changed its title to Journal and Proceedings. Liversidge also served as the society’s Honorary Secretary from 1874 to 1884, and he designed the Seal required for its NSW Government Act of Incorporation in 1881.

English pastor and geologist William Branwhite Clarke published 15 papers in the journal between 1867 and 1878. These included the RSNSW’s Inaugural Address, in which he argued that science, with its focus on factual evidence, was superior to the philosophy promoted by preceding NSW intellectual societies. He later published six Anniversary Addresses and research reports on minerals in north Queensland, fossils of kangaroos and extinct birds, ocean depth soundings, and some effects of forests on Australia’s climate.

During Liversidge’s term as the journal editor, English science educator William Adam Dixon wrote a series of worthy articles on chemistry, mineralogy and palaeontology: highlighting islands of sea-bird guano, NSW deposits of silver, nickel, cobalt and coal, and chemical aspects of orchids, ferns and native coastal species. Other writers on Australian fossils, rocks, minerals, shells, fish, fauna, plants and forests included William James Barkas, Robert Etheridge Junior, Australian Museum curator Johann Ludwig Gerard Krefft, Royal Mint assayer Carl Leibius, botanist Charles Moore and priest-geologist Julian Edmund Tenison-Woods.

KANGAROOS SKETCHED BY GERARD KREFFT, FIRST CURATOR OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM [MITCHELL LIBRARY, STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES]

Liversidge also encouraged articles about Aboriginal knowledge and culture. He published Peter MacPherson on Aboriginal astronomy, language, oven-mounds and stone implements; Peter Beveridge on Aboriginal people of the Murray-Darling basin, and ‘Notes’ by John Fraser and James Manning. These followed Transactions articles on Polynesian and New Guinea populations, reported by Scottish educator John Dunmore Lang.

Despite the RSNSW’s stated objectives to further knowledge in Science, Philosophy, Art and Literature, no articles on philosophy or literature, and only a few on arts and crafts, were published in the first 20 years of the journal. These included several papers by Ludovico Wolfgang Hart on ‘the rise and progress of photography’ as a matter of importance to Australian education; John Plummer on art instruction; Italian pianist Jules Meilhan on the transformative power of classical music; Emerich Reuter Roth on rational construction of chairs and desks, and William Henry Warren on the strength and elasticity of ironbark timber for construction projects.

As the gold boom boosted Australia’s population and prosperity, Liversidge introduced some farsighted concepts for public welfare, infrastructure and economic development. Frederick Norton Manning, director of the asylum at Gladesville, illuminated journal readers on ‘causes and prevention of insanity’, while Alfred Roberts discussed ‘pauperism’ and hospital accommodation. Engineers James Manning, Charles Mayes, John Smith and A. Pepys Wood wrote on how to improve the colony’s water supply and sanitation. NSW Auditor-General Christopher Rolleston assessed crime statistics and new post office, banking, credit and insurance systems.

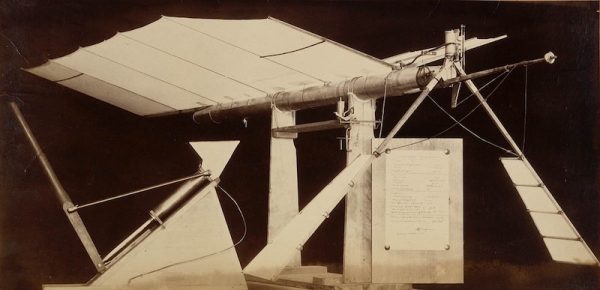

Several RSNSW writers presciently highlighted nascent technologies that would underpin modernity through the 20th century. Edward Charles Cracknell highlighted international advances with the ‘electric telegraph’; George Denton Hirst focused on new optical lenses made by Carl Jeiss (Zeiss) in Germany, and Lawrence Hargrave presented his prescient ideas and designs for ‘flying-machines’.

Hargraves’ first RSNSW JProc articles were published in 1885 and 1886; 17 years before American inventors Orville and Wilbur Wright flew the world’s first successful motorised aeroplane in December 1903. Yet Hargrave was only one example of how many young, well-educated British immigrants pioneered worldwide advances after they settled in Sydney in the mid 19th century. The Royal Society of New South Wales, via its annual Transactions, then Journal and Proceedings, was a vital conduit for their intellectual pursuits.

MODEL OF ONE OF LAWRENCE HARGRAVE’S LATE 19TH CENTURY ‘FLYING-MACHINES’ [STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES]

For broader detail about the early years of the RSNSW and work of colonial scientists, read The Long Enlightenment: Australian Science from its Beginnings to the Mid-20th Century, by Emeritus Professor Dr Robert Clancy FRSN (Halstead Press, 2021).

0 Comments