Daphne Mayo (1895-1982)

Written by Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Volunteer

To celebrate Women’s History Month in 2020, the Royal Australian Historical Society will continue our work from last year to highlight Australian women that have contributed to our history in various and meaningful ways. You can browse the women featured on our webpage, Women’s History Month.

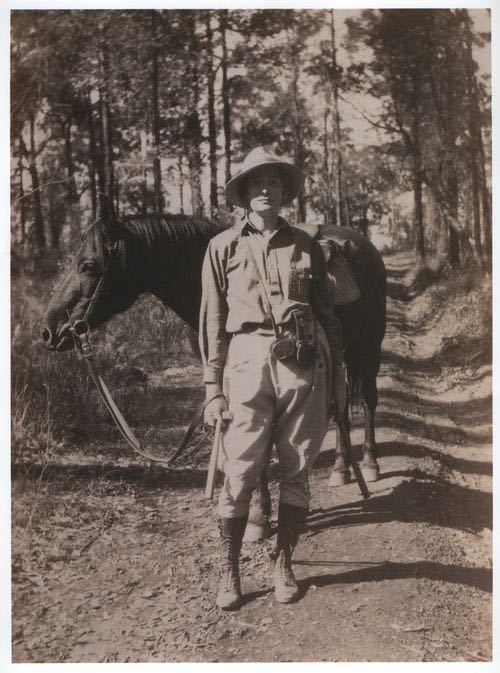

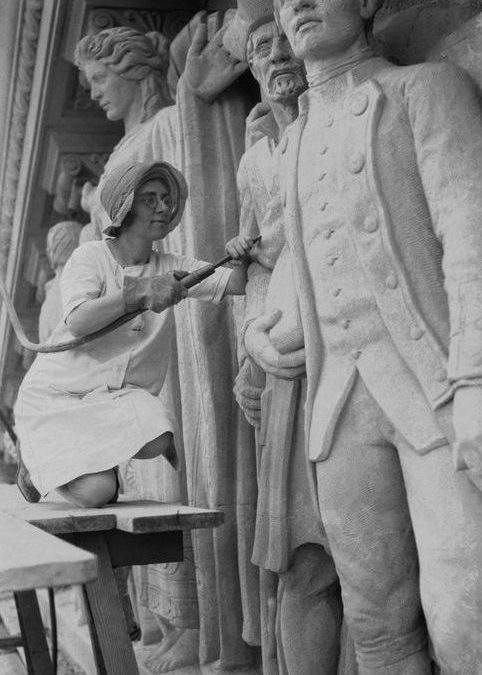

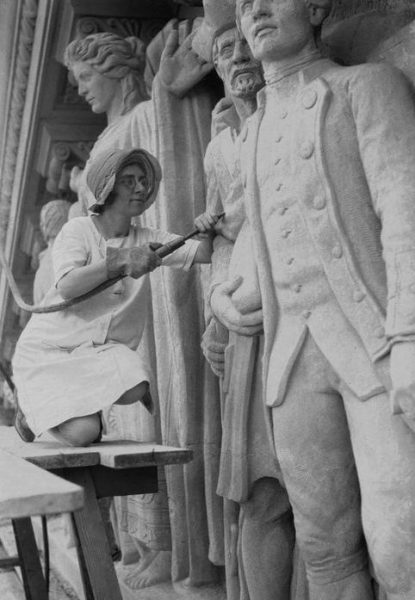

In 1927, popular women’s magazine Woman’s World published a profile on an emerging young female sculptor. “She is such a little bit of a thing,” they reported, “that one half expects the wind to pick her up and carry her off. Yet she can hew and mould and chisel” as well as any man. [1]

The woman was Daphne Mayo, celebrated today as Queensland’s most significant female sculptor, and one of the country’s leading woman artists of the twentieth century.

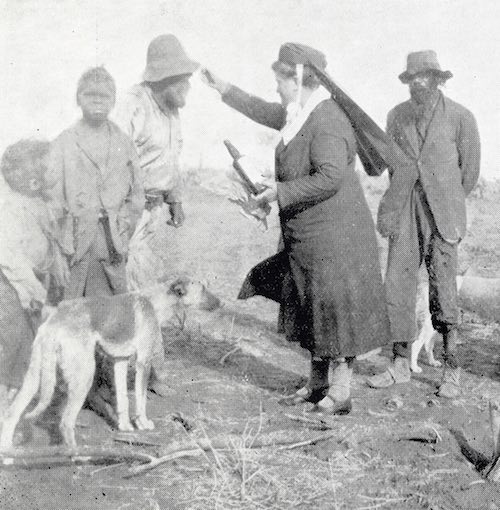

Daphne Mayo working on the Brisbane City Hall tympanum, c. 1930 [Image courtesy University of Queensland Fryer Library, UQFL119]

Graduating in 1913, the following year Daphne was awarded Queensland’s first publicly funded travelling art scholarship. Though her departure overseas was delayed for five years by World War I, she made the most of her extra time in Australia, attending Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School and working on her stone carving skills under Frank Williams.

In 1919 Daphne set off for London, briefly attending the Royal College of Art before entering the Sculpture School of the Royal Academy of Arts in December 1920. She graduated three years later with the school’s gold medal for sculpture and the Edward Stott Travelling Studentship to Italy. Her time in Rome was cut short by her brother’s death in 1924 and in June 1925, Daphne returned home, broke off her engagement with fellow artist Lloyd Rees, and launched headfirst into her career. [3]

Daphne made headlines for her numerous public commissions during the late 1920s and 1930s. She carved, in situ, the Queensland Women’s War Memorial in Anzac Square, relief panels for the chapel at the Mount Thompson Crematorium, and, perhaps her greatest work of all, the Brisbane City Hall tympanum between 1927 and 1930.

During these years she also made great strides towards enhancing the artistic reputation of her home state. Along with her close friend, painter Vida Lahey, she founded the Queensland Art Fund in 1929. She and Vida also oversaw the establishment of the state’s first art reference library in 1936. Daphne also organised Brisbane’s first significant loan exhibition in over a decade in 1930, and helped obtain for the Queensland National Art Gallery the Godfrey Rivers Trust in 1932, a collection honouring the work of her teacher from over two decades ago. [4]

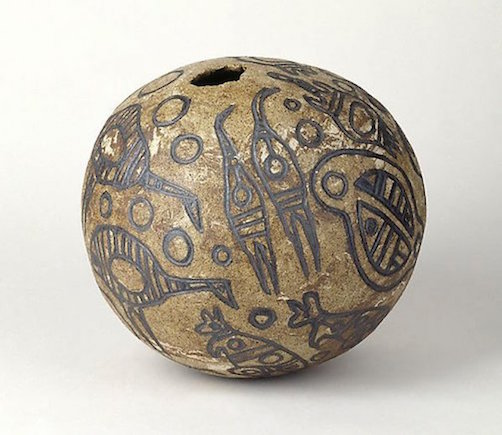

Daphne moved to Sydney during the Second World War and though she no longer worked on large-scale public commissions, her artistry continued to flourish. She turned to portrait sculpting, including the bust of her once-fiancé Lloyd Rees along with a number of other subjects. Olympian, a half-body female sculpture carved in 1946 and cast in bronze after 1958, is one of her more famous works from this period. [5]

Daphne Mayo, Olympian c.1946, cast after 1958, bronze, 94.5 x 31.5 x 23cm, Queensland Art Gallery

She was appointed a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in 1959 and upon her return to Brisbane, Queensland Art Gallery’s first woman trustee in 1960. Between 1961 and 1965 Daphne completed her final major commission of a statue of Sir William Glasgow. Her delayed completion led some media outlets at the time to paint her as an eccentric old woman unfit for the task – but at seventy years old, with the help of assistants, Daphne finished the statue and proved them wrong. [6]

After her death in 1981 at the age of eighty-five, Daphne continued to be honoured amongst her peers and admirers. The University of Queensland conducts a biennial Daphne Mayo Visiting Professorship in Visual Culture; St Margaret’s School, her alma mater, hosts the biennial MAYO Arts Festival and Friends of MAYO who fundraise to acquire artworks for the school. The Queensland Art Gallery held a retrospective exhibition of her sculpture in 2011, thirty years on from her death. Sculptors Queensland honours her as a “cultural icon”. [7] For as small and unassuming a woman as Daphne was, she took the male-dominated world of sculpture by storm. Australian art has not been the same since.

References:

[2] Judith M. McKay, ‘Biography – Lilian Daphne Mayo’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2012, <http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mayo-lilian-daphne-14954>, accessed 2 March 2020.

[3] McKay, ‘Biography’.

[4] McKay, ‘Biography’.

[5] ‘Olympian – Daphne Mayo’, QAGOMA Learning, <https://learning.qagoma.qld.gov.au/artworks/olympian/>, accessed 3 March 2020.

[6] McKay, ‘Daphne Mayo’, p. 7.

[7] ‘Daphne Mayo Visiting Fellowship’, University of Queensland, <https://communication-arts.uq.edu.au/daphne-mayo-visiting-fellowship>, accessed 3 March 2020; ‘Daphne Mayo’, St Margaret’s, <https://www.stmargarets.qld.edu.au/125/125-notables/daphne-mayo>, accessed 3 March 2020; ‘Daphne Mayo’, QAGOMA, <https://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/whats-on/exhibitions/past-exhibitions/daphne-mayo>, accessed 3 March 2020; ‘History’, Sculptors Queensland, <https://sculptorsqld.org.au/about/history>, accessed 3 March 2020.