Knowledge for a Nation: Origins of the Royal Society of New South Wales

A new book by the Royal Society of NSW reveals colonial research culture in New South Wales.

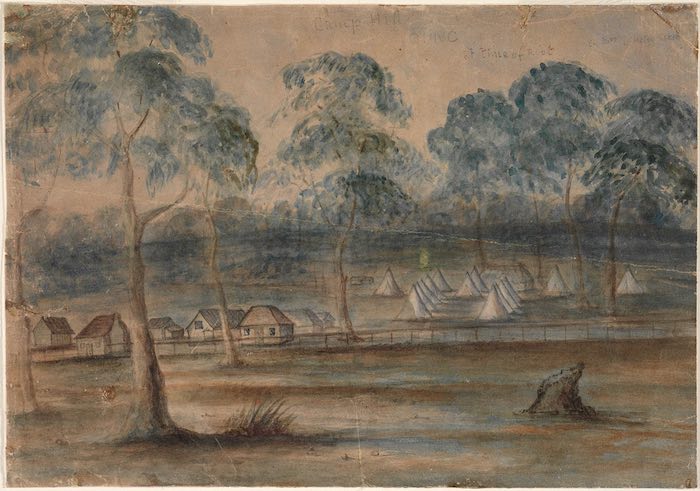

During the reigns of British monarchs George III, Queen Victoria and Edward VII, the prison colony of New South Wales was transformed by intellectually curious and innovative migrants from Britain, Europe and America.

In a new book, Knowledge for a Nation: Origins of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Blue Mountains historian Dr Anne Coote explains how leading colonial administrators, scientists, engineers, doctors and other ‘natural philosophers’ gathered to share their discoveries of the Antipodean continent and their experiments with radical new technologies like the electric telegraph, photography, railways and flying machines.

Dr Coote summarised her research in an illustrated presentation at the State Library of NSW on 2 October 2024. Her book was commended by the NSW Governor, Her Excellency Margaret Beazley, State Librarian Dr Caroline Butler-Bowdon, the RSNSW’s President, Dr Susan Pond, and Vice-President, Emeritus Professor Peter Shergold.

Knowledge for a Nation highlights several dozen ‘gentlemen savants’ who established the colony’s first learned societies, university, museums, observatories, public library, art gallery and botanical research centre.

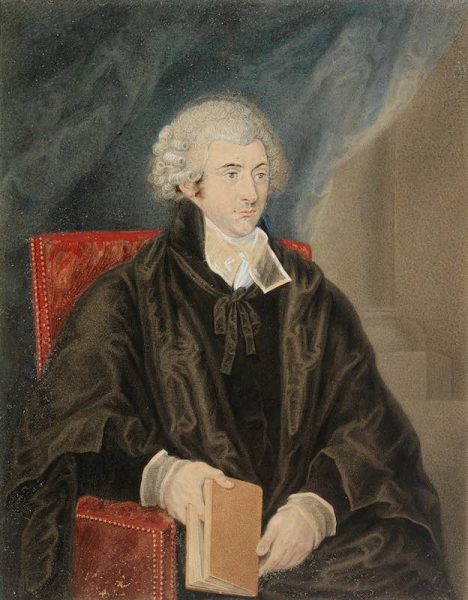

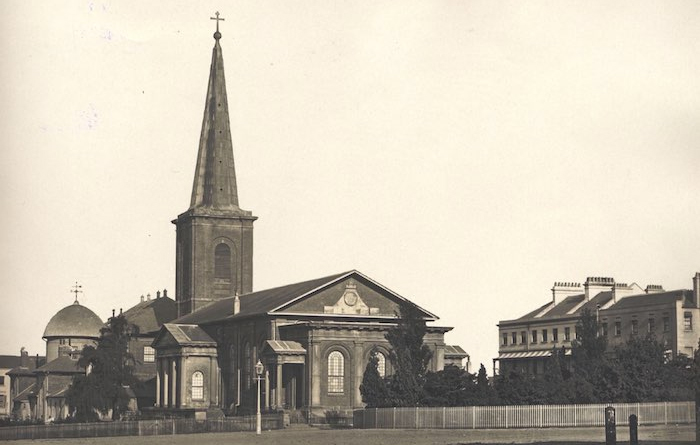

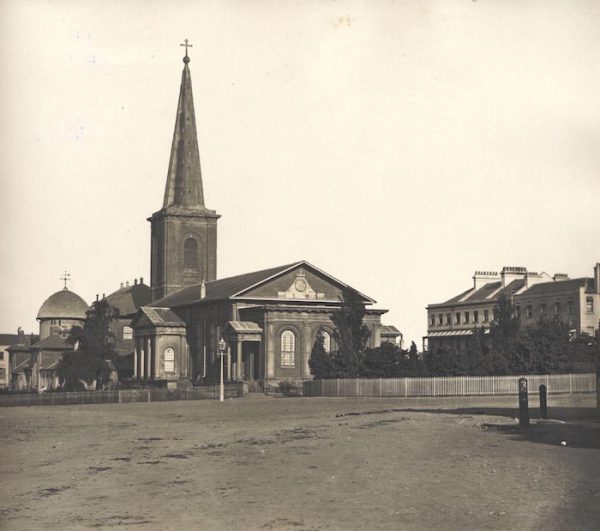

After Governor Lachlan Macquarie was recalled to Britain in 1821, his replacement in Sydney, the mathematician and astronomer Thomas Brisbane, became the inaugural Honorary President of the Philosophical Society of Australasia, the colony’s first formal scientific institution. The founders of this short-lived group included Surveyor-General John Oxley, merchants Edward Wollstonecraft and Alexander Berry, hydrographer Phillip Parker King, astronomer Christian Rümker, judge Barron Field and surgeons Patrick Hill and Donald Macleod.

Although the Philosophical Society evaporated only a year after its first meeting, several later societies were replaced in 1866 by today’s Royal Society of New South Wales, which has more than 700 members and fellows.

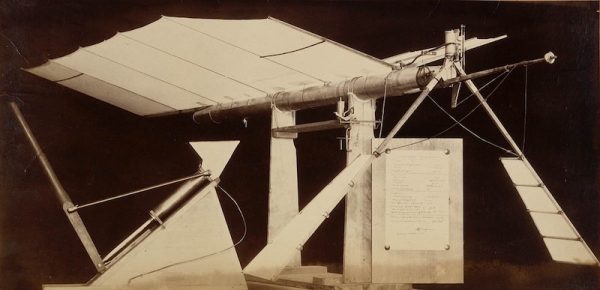

Dr Coote’s history of these societies introduces many leaders of NSW intellectual culture during the Regency, Victorian and Federation periods—men like aviation pioneer Lawrence Hargrave, whose box kites inspired the Wright brothers; Henry Chamberlain Russell, who led the Sydney Observatory and published the colony’s first regular weather tables and reports about new stars and comets; Australian Museum curator Gerard Krefft, who collected and recorded local frogs, snakes and birds’ eggs; Sydney University’s first Dean of Science, Archibald Liversidge, and Professor of Geology, Edgeworth David, and the government’s Chief Railway Engineer, Henry Deane.

Women were excluded from learned societies during the nineteenth century, except for some mixed-gender social events, called ‘conversaziones’, which the RSNSW held at Sydney University’s Great Hall. But Dr Coote’s book identifies some notable women (mainly daughters of successful Sydney men) who made significant contributions to scientific research and publications. They include botanists Sally Hynes and Jean White, botanical illustrators Helena and Harriet Scott, physicist and chemist Jane Foss Russell and Cambridge-educated physicist Florence Martin.

Knowledge for a Nation: Origins of the Royal Society of New South Wales is a 320-page paperback volume. It is available from the State Library shop, selected bookstores and online retailers, and can be ordered via the RSNSW website royalsoc.org.au.

This book was supported by the Create NSW Cultural Grants Program, a devolved funding program administered by the Royal Australian Historical Society on behalf of the NSW Government.

The 2023 NSW Premier’s History Awards, with $85,000 in prize money, were announced at the State Library of NSW on Thursday, 7 September.

The 2023 NSW Premier’s History Awards, with $85,000 in prize money, were announced at the State Library of NSW on Thursday, 7 September.