Written by Elizabeth Heffernan, RAHS Volunteer

To celebrate Women’s History Month in 2021, the Royal Australian Historical Society will continue our work from previous years to highlight Australian women that have contributed to our history in various and meaningful ways. You can browse the women featured on our webpage, Women’s History Month.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this webpage contains the images and names of people who have passed away.

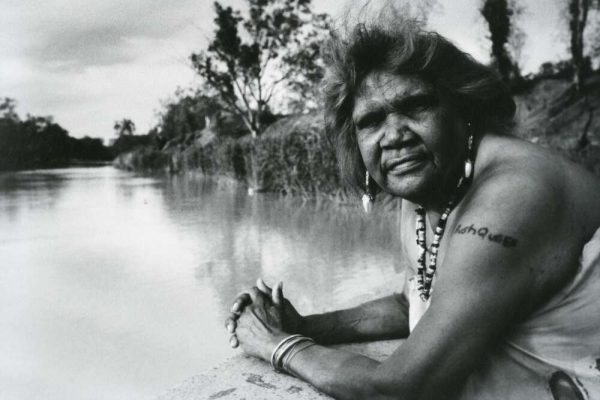

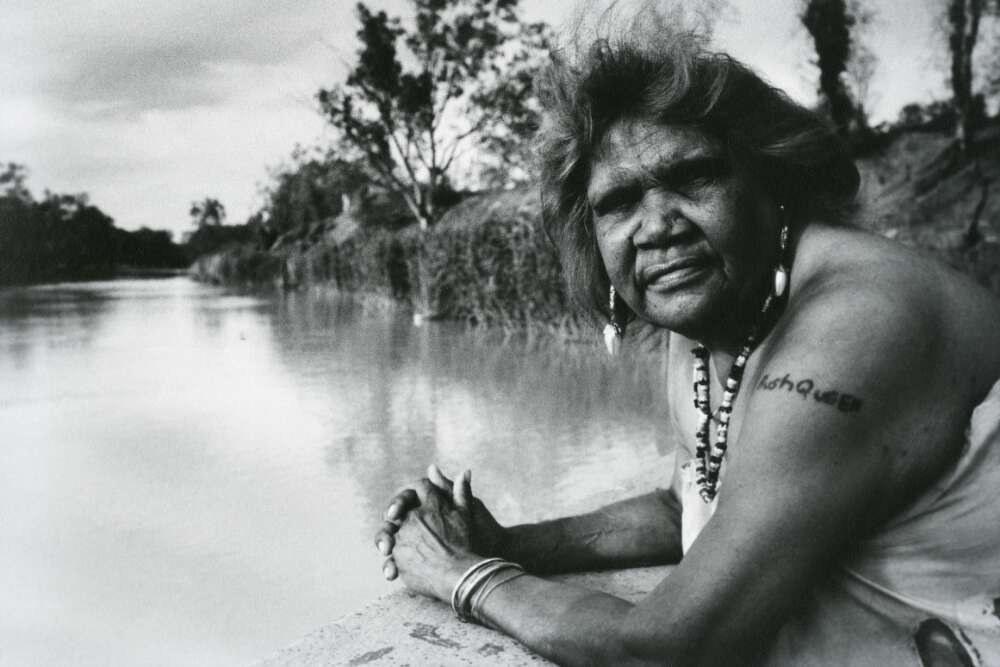

Affectionately known as the Bush Queen of Brewarrina, Muruwari community worker and filmmaker Essie Coffey left an indelible mark on Australian politics, arts, and culture. Born Essieina Goodgabah in northern New South Wales, Essie spent her childhood travelling between stations with her father. She learned droving, woodcutting, and how to break in wild horses across a series of rural communities. [1] Such early life experiences imbued her with a strong sense of bush identity that would persist throughout her lifetime.

ESSIE COFFEY PHOTOGRAPHED AT BREWARRINA IN 1991 BY LORRIE GRAHAM. NOTE THE ‘BUSH QUEEN’ TATTOOED ON HER LEFT SHOULDER. [IMAGE COURTESY NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA, NLA.OBJ-152764120.]

In the 1950s, Essie married Albert ‘Doc’ Coffey. Soon afterwards they moved to Brewarrina, also known as ‘Dodge City’, in the north-west slopes of NSW. Together they raised eighteen children, ten adopted. In 1969 the Coffeys moved to the west Brewarrina reserve, where Essie pursued advocacy for the community and her people.

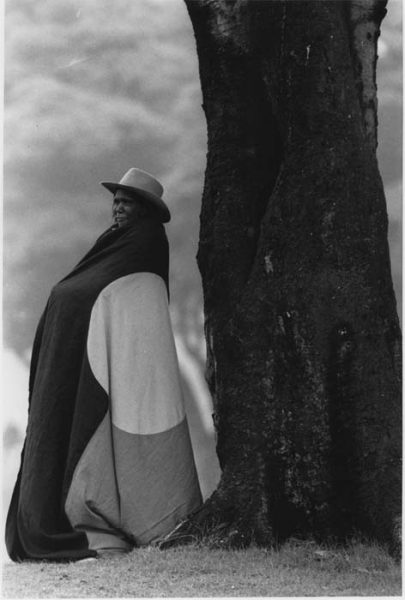

Among her many remarkable achievements, Essie co-founded the Western Aboriginal Legal Service in the 1970s. She was also an inaugural member of the National Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, helped establish the Aboriginal Heritage and Cultural Museum in Brewarrina, and was on the board for the NSW Aboriginal Lands Trust, the NSW Aboriginal Advisory Council, and the Ngemba Housing Cooperative in the 1990s. On a more local scale, Essie also helped create the first women’s knock-out football team in the state’s northwest. [2]

ESSIE COFFEY WEARING THE ABORIGINAL FLAG. [IMAGE COURTESY BALLAD FILMS.]

In her thirties Essie became involved in filmmaking and discovered another passion that would fuel her later life. Alongside documentary filmmaker Martha Ansara, she made the award-winning film My Survival as an Aboriginal in 1978. It details her life in Brewarrina, tackling the ongoing issues of colonialism and dispossession suffered by the Aboriginal community. Essie gave a copy of the film to Queen Elizabeth II at the opening of Australia’s new Parliament House in 1988. The sequel, My Life as I Live It, premiered in 1993 and returns to Brewarrina fifteen years later. Most importantly, My Life highlights the Community Development Employment Program making a difference to the remote township and demonstrating the values of community, dignity, and self-determination Essie upheld her whole life. [3]

Essie received the Order of Australia (OAM) medal in 1985. Though also nominated for an MBE, she refused, on the grounds that “I’m not a member of the British Empire.” [4] Essie endured renal failure in the final years of her life, and passed away in 1998. Her struggle with kidney disease featured poignantly in Darrin Ballangarry’s documentary Big Girls Don’t Cry. The title, an affirmation from Essie’s own family in the film, beautifully summarises Essie’s strength, determination, and passion for life, values which persist alongside her memory today. [5]

References:

[1] ‘Essie Coffey’, Koori Web: Heroes in the Struggle for Justice, http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/heroes/biogs/essie_coffee.html, accessed 8 February 2021; ‘Essie Coffey’, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.portrait.gov.au/people/essie-coffey-1940, accessed 8 February 2021.

[2] ‘About Essie Coffey’, Ballad Films, http://www.balladfilms.com.au/Essiebiog.html, accessed 8 February 2021; ‘Coffey, Essie’, The Australian Women’s Register, https://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/IMP0121b.htm, accessed 8 February 2021.

[3] ‘My Survival as an Aboriginal’, Ballad Films, http://www.balladfilms.com.au/films/my-survival-as-an-aboriginal/, accessed 8 February 2021; Romaine Moreton, ‘My Survival as an Aboriginal: Go Away’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/my-survival-aboriginal-go-away, accessed 8 February 2021; ‘My Life as I Live It’, Ballad Films, http://www.balladfilms.com.au/films/my-life-as-i-live-it/, accessed 8 February 2021; ‘Essie Coffey’, National Portrait Gallery.

[4] ‘Coffey, Essie’.

[5] ‘Big Girls Don’t Cry (2002)’, Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, https://caama.com.au/catalogue/big-girls-dont-cry-2002, accessed 8 February 2021.

0 Comments